Epilepsy and its seizures: causes, types, and management

Autore:Epilepsy is a neurological condition that is characterised by seizures, which can cause a range of behaviours such as tremors, loss of consciousness, or ‘blanking out’. In this article, a leading London neurologist explains all you need to understand about epilepsy and epileptic seizures.

What causes epilepsy?

There is no clear cause for epilepsy. It can be genetically passed, or caused by strokes, brain tumours or trauma, substance abuse, dementia, brain infection, or a lack of oxygen while being born – but for most people with epilepsy, the cause is unknown. Seizures can happen outside of having epilepsy and can be a singular event, but those who experience a seizure for the first time should still seek medical attention so that the underlying cause can be discovered. Seizures are bursts of neuroelectric activity that can interrupt function in a variety of ways. Epilepsy can develop at any age, but typically initially manifests either in childhood or in older age, and tends to be a lifelong condition – however, it can become better and less obstructive over time with management, to the point that seizures are very infrequent with years in between each one and they are not easily triggered.

What are epileptic seizures?

Some types of epileptic seizures include:

- Simple partial (focal) seizure, which can feel like a ‘flip-flop’ in the stomach (like when on a ride or plane), a déjà vu, tingling, unusual tastes or smells, or a stiffness and twitching in a part of the body. These seizures can forecast a different seizure.

- Complex partial seizure, where an individual may begin to make involuntary and repetitive movements like rubbing their hands, swallowing, smacking their lips, and making random noises. Unlike a simple partial seizure, the individual will not be responsive during this and will not retain memories of it.

- Tonic-clonic seizures, previously known as ‘gran mal seizures’, are what most people are familiar with when they think of epileptic fit. It happens in two stages, the tonic, where the individual loses consciousness and their body goes rigid (and likely to fall to the floor), and the clonic, where there is involuntary jerking and shaking, and individuals may bite their tongue or lose control of their bladder and bowels. They tend to last a few minutes, and afterwards, the individual will likely feel drained and confused with no recollection of what just happened. The tonic and clonic portions can also happen independently as their own type of seizure.

- Absence seizures, where the individual may appear to be lucid but they lose awareness of their surroundings for a period. They will stare into space and not reach to stimuli or to attempts to get their attention. They may tremor slightly. These seizures only last a few seconds but can happen several times a day.

Seizures can last for a few seconds or extend to over five minutes, and sometimes they can happen one after the other. In the case of constant or prolonged seizures, it is advised to seek emergency medical attention immediately.

For most people with epilepsy, there may not need to be a trigger for a seizure, but for others, they may triggered by a lack of sleep, too much stress, drinking alcohol or using substances, menstruation, or flashing lights.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

Individuals are usually only diagnosed as having epilepsy if they have more than one seizure and are seeking medical attention, or if the doctor – particularly a neurologist – believes they are likely to have more seizures in the future.

The diagnostic process involves a neurologist asking investigative questions, about things such as family medical history or if the individual has had illnesses or injuries prior that could have caused epilepsy. They will also ask about the individual’s experiences, such as their behaviour and feelings, whilst seizing. This will include questions about what was happening before the seizure, its effects on memory, and possible triggers.

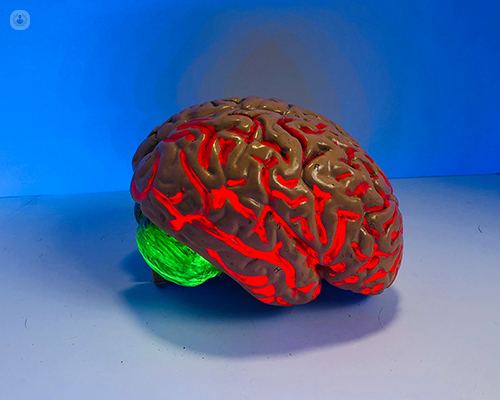

In addition, they may conduct a few tests to see the condition of the brain. There is no one specially designed test for epilepsy, so they may choose to conduct an MRI to see the structure of the brain, or an electroencephalogram to check on the brain activity. If they suspect that the cause of the epilepsy is not neural and is due to genetics, they may instead do a blood test. However, even if the results from these tests don’t say that anything is wrong, the individual can still have epilepsy solely due to the fact that they have or will have multiple seizures.

How is epilepsy treated?

Epileptic seizures can be managed to be less frequent or to be stopped completely with a variety of methods:

- Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs), which help most patients and work by altering the levels of brain chemicals. They are not suitable for all people with epilepsy, especially those who are or are planning to be pregnant. They are taken orally and daily.

- Surgical removal or destruction of the part of the brain that causes seizures, which is an option that is explored primarily if AEDs were ineffective. The part that is excised may just consist of a tumour (if it is the culprit) or where there is cerebral damage.

- An implanted electrical device to control seizures. This could be a device implanted in the chest, similar to a pacemaker, called vagus nerve stimulation, where the electrical signals in the brain are altered by wires that go under the skin and connect to the vagus nerve in the neck – or, a device implanted into the brain with electrodes that perform the same way, called deep brain stimulation.

- A specific diet, called a ketogenic diet, which is high in fats and low in carbohydrates and protein, and affects the chemicals in the brain. This was one of the earliest ways to treat epilepsy, but it is not so common since the invention of AEDs and due to a high-fat diet being considered unhealthy. This method may be used for children with epilepsy who are too young for AEDs or surgery.

Individuals with recognisable triggers for their seizures should take care to avoid or reduce their exposure to those triggers, such as strong smells, flashing lights, and stressful situations.

If you have experienced seizures and would like to explore treatment and formal diagnosis, consult with a neurologist on Top Doctors today.