Vitreomacular traction

Mrs Kapka Nenova - Ophthalmology

Created on: 04-24-2020

Updated on: 03-27-2023

Edited by: Conor Lynch

What is vitreomacular traction?

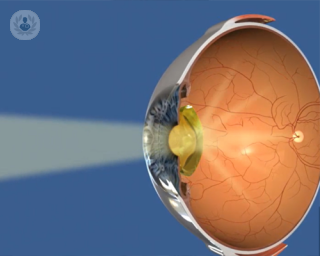

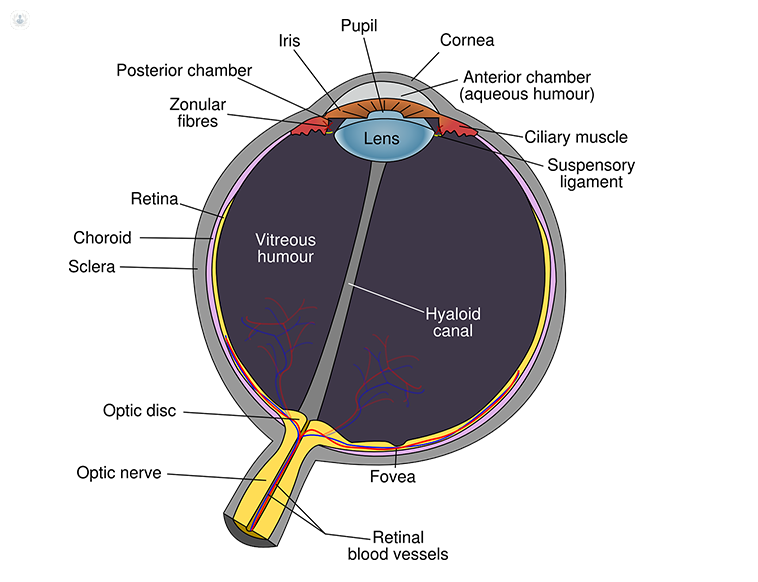

In the middle of your eye, there is a substance called vitreous. In a healthy eye, this substance is a clear gel - mainly made up of water and collagen - attached to the macula and the retina and helps maintain your eye’s shape. When we look at an object, light travels through the vitreous and focuses onto the retina at the back of the eye.

As we age, the vitreous can sometimes separate from the retina and cause a condition known as posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). Sometimes, the vitreous doesn’t come away completely, leaving some of the gel attached and pulling on the macula. This then results in vitreomacular traction (VMT). If this condition is left untreated, the damage can lead to a macular hole and vision loss.

What causes vitreomacular traction?

In young, healthy eyes, VMT is uncommon and is typically seen in patients above the age of 70. The cause of VMT is due to part of the vitreous remaining attached to the macula. There are some eye diseases that can increase your risk of developing it.

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- Diabetic eye disease

- Myopia

- Retinal vein occlusion

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptoms of patients with VMT include:

- Distorted vision (metamorphopsia) that makes a grid of straight lines appear wavy or blank

- Flashes of light in the eye

- Decreased sharpness of vision

- Seeing objects smaller than they actually are

The symptoms may be mild, develop slowly, and can present independently. For example, you may experience distorted vision but without a reduction in the sharpness of your vision.

How is it diagnosed?

Your ophthalmologist will need to look inside your eye using one or more of the following tests:

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT) - an imaging test that takes pictures of the retina’s layers and helps show how much damage has occurred to the macula.

- Fluorescein angiography - this is another imaging test that takes photos of your retina. A yellow dye is also injected into your vein in your arm. This will allow your ophthalmologist to see how well the blood circulates inside your eye and identify any swelling of the macula - a common sign of VMT.

- Ultrasound scan - by using sound waves, your ophthalmologist gets a better view of the inside of your eye and how well the vitreous and macula are attached to one another.

How is it treated?

There are a few options for treating VMT. Your ophthalmologist will use one or more of the following approaches:

- Wait and see - as some cases of VMT spontaneously resolve, your ophthalmologist might wait and regularly monitor your eye to see if any changes occur. This option is often chosen if your symptoms aren’t serious enough to warrant an intervention.

- Pars plana vitrectomy surgery - For some patients, their vision might be badly affected which means that they will need to undergo a vitrectomy. The surgery involves manually releasing the vitreous from the macula. As it is quite an invasive treatment, it is reserved for those who are at risk of severe visual disturbances and blindness.

- Medication - If you aren’t suitable for vitrectomy surgery, then you may be given medications instead. The medication used is called ocriplasmin and is given by injections into the centre of the eye. It works by dissolving the protein fibres that connect the vitreous and macula together.

Which specialist treats vitreomacular traction?

A specialist that can treat vitreomacular traction (VMT) is an ophthalmologist.